|

|

‘They Were Not Told Where They Were Going’

(As Nov. 11 draws close, this slice of history, written some years ago by Margaret Holmes is being re-printed to remind younger readers about Canadians serving their country during WWII.)

When George Holmes first left for Calgary he thought I should stay in Provost until the regiment was moved to permanent quarters, but in a couple of weeks he was writing for me to come to Calgary. Many of the men already had their wives there — besides, he was lonesome!

I travelled by train to Edmonton and then down to Calgary. People there were being urged to rent out their extra rooms, and we were surprised at some of the strange places that were offered. Some were in poor areas of the city and some were just plain grubby. We decided on a place in the basement of an elegant old house on a nice street. It had been converted into “suites”. We had one room and a shared bath with another “suite” across the hall. The furnishings were clean and good but it was quite a change for us to live in one room in a basement. The closet had been turned into a mini-kitchen with cupboards and a two-burner hot plate for a stove. We kept our milk and perishable food upstairs in the landlady’s refrigerator. She was a nice woman and the other tenants were friendly.

George and I were away from our families for the first time in our lives. The worry of actual war was not yet in our minds, as no soldier was shipped overseas until he had completed basic training and that took several months. We were excited by the new life, we met new friends, mostly those connected to the “Reckies”.

|

Jack Martin had stood in line directly behind George at their induction. George was number M51048 and Jack M51049. This number was stencilled on their equipment, in their pay book, and on the “dog tags” they were required to wear, at all times, around their necks. Jack and Eunice Martin have been our friends ever since. They lived then in a tiny one room apartment in downtown Calgary, with a Murphy bed that folded up into a cupboard. Jack had a Morris Minor car and it was an amusing sight to see his 6' 4" frame unfold from inside that little car. There were several other couples that we were friendly with, but we gradually lost track of them after the war.

We went to movies occasionally, we visited among ourselves but we were all living on army pay so were generally pretty frugal. A corporal received $1.25 per day. If he lived off the base he would get a food allowance but this was not often allowed, the soldier required permission from his officer to do so. Passes were given out in hourly units. A 24 hour pass was the usual pass, at a weekend, a 48 hour perhaps would be allowed once a month. A soldier's wife received $75 monthly, which was considered sufficient for her support. These of course were 1942 dollars, worth a good deal more than at present. The men referred to their jobs in the army as “Working for George”. The George was King George VI, of England.

In the fall of 1942 the regiment was moved to Nanaimo, B.C. They travelled by troop train and the families followed later. The wives were allowed a cheap rate on the train because they were soldiers' dependents. The trains loaded with troops were given preference on the railway and civilian trains would be sidetracked to allow a troop train to speed through. We were happy to be going west, rather than east. East brought men closer to the ports where soldiers were shipped out across the sea to Europe.

We found however at the West coast the prime worry was the Japanese conquests in the Pacific. We had heard with shock in our room in Calgary, the famous and oft repeated radio speech of the United States President Franklin Roosevelt, his voice shaking with emotion, calling the attack on Pearl Harbour “A day of Infamy”. Japan had gone on to win island after island, Hong Kong had fallen with disastrous losses to our own Canadian troops. There was genuine fear on Vancouver Island that Japan was winning the Pacific war. Alaska had been bombed. Perhaps we were closer to the war here than anywhere in Canada.

In Nanaimo George was promoted to acting sergeant. I and other Reckie wives, took rooms in an auto court not far from the base. They were poor, shabby buildings and would not have been fit to live in during winter, but the men were moved again in a few weeks to Sooke, south of Victoria. They marched all the way, making camp in tents at nights en route, wherever accommodation could be arranged and carrying all their personal gear. Wives followed later on the train, and had the task of trying to find accommodation in Victoria. (Sooke, at that time, was a village with no place for us to live). The army had lists of rooms to let, that we could use in our search. The rooms varied from fair to bad. We learned quickly that soldiers’ wives were not liable to find anything very pleasant. Landladies were not eager to have transients such as us, and would much rather have workers from the shipyards or factories who would not be transferred in a short while. We were preferred to sailors, or sailors’ wives. They were the least appreciated. The big navy base at Esquimalt with sailors home from sea duty, ready to raise a bit of Cain after being months at sea, had left many of the natives with an aversion to navy men, or their women.

I decided on a room on York Street. Again it was a big house, turned into rooms to rent. There was no central heating and the bathroom shared with the other tenants, had a long list of “Don’ts” posted on the wall. Our room was heated by a small wood burning stove, and I found that the wood sticks were counted and if you foolishly burned them early in the day you would have a cold night. I felt cold constantly in that damp, dull climate. Sooke was about 30 miles from Victoria. An army truck would bring those soldiers, who had passes, into Victoria and pick them up early in the morning to take them back to the camp.

The landlady, we soon found, was an unpleasant woman, and we looked for a new place. We found another auto court near the outskirts of the city. (Auto courts were not under one roof as the present motels are. They were small separate buildings grouped around a central parking space.) We had two small rooms in the court but no bathroom. It was in the central area where a little store shared a building on one side with the bathrooms on the other. The place had a variety of renters, some soldiers’ families, some from the shipyards, or the saw mills, and some sailors’ families. It was for the most part quiet and the people living there were friendly and pleasant. Occasionally the sailors had a loud party, and I came to understand why they weren't eagerly sought by landladies.

The city of Victoria was under a blackout, as all coast cities and towns were. No light was to be shown after dark, no street lights were lit, and the whole area was dark and quiet. We seldom went anywhere at night. There was fear that the shipyards would be one of the prime targets for Japanese planes or submarines. All the Japanese Canadians* who had been living in Victoria, and along the coast of B.C. had been moved inland because of fear that they would act as spies for Japan. We didn't hear much about it at the time and it was years later before we realized the extent of their suffering where they were relocated and how the families were separated. Their houses and businesses were confiscated and they were poorly paid. The people of B.C. had very little sympathy for them, and considered the government had done the right thing. They were frightened and under the circumstances, rightly so. They should not have cheated the Japanese Canadians in the manner that they did. Most of the relocated were completely loyal to Canada.

When Christmas arrived George was posted for duty on Christmas Day, but the commanding officer arranged for wives of those on duty to be allowed to have Christmas dinner at the camp.

An army transport picked us up from our various homes. We sat on benches in the back of the truck and felt it was quite an adventure.

I joined George in the Sergeant's Mess and we had a traditional turkey dinner and plum pudding. I really can't remember whether it was tasty or not. I think I was nervous and ill at ease. I was in the early months of pregnancy and having squeamish spells and afraid I might embarrass myself.

The winter was unusually cold in B.C. that year, as it was also in Alberta. There was snow on a couple of occasions and exposed pipes froze. George was notified that his father was sick in hospital and was given a week's leave to go and visit him, shortly after Christmas. On his way back he was more than a day late as the trains were freezing up and being delayed. It was 60 degrees Fahrenheit below in Edmonton when he waited there for the train. He sent a telegram to the C.O. (commanding officer) to explain it, so he wouldn't be charged with being A.W.O.L. (absent without leave). The paper at Provost was shut down for a few weeks while his father convalesced.

George was disappointed that he wasn't able to get into radio work in the regiment and decided to try to get a transfer to the Signal Corps. It had to go through official channels and took some time. He was told he would not be allowed to keep his third stripe if he moved. He regretted this but the chance of working in signals meant more to him, so he decided to transfer. He would get more pay, as a tradesman received 50 cents more per day, and he would also be allowed to live off base.

We moved to Vancouver in the spring. At that time the boat to Vancouver left from a dock in front of the Empress Hotel. We boarded in the evening, took a stateroom and slept overnight. The boat was quite luxurious, with a dining room similar to a good hotel. It docked right in the centre of Vancouver, the next morning.

George reported to his new C.O. and was assigned to a depot on Georgia St. It was quite different than being with the regiment, more like a civilian job. We didn't become friends with his co-workers as they lived in various places in the city and the ties were much looser. We found a place to live near English Bay, two big gloomy rooms in an old mansion.

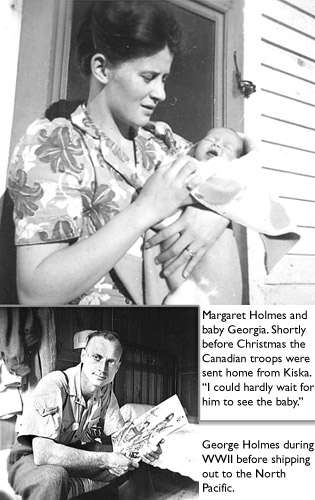

Vancouver in the spring is a beautiful place with gardens full of blooming bushes and flowers. We enjoyed living there, and George’s C.O. had assured George he would not be liable to posting overseas until later in the year, after the expected baby had arrived. It was a shock in June when he was required to replace a soldier who had gone absent, as a Canadian outfit was being sent out to join an American group, enroute somewhere in the Pacific. They were not told where they were going. They presumed it to be Alaska because of the gear and clothing they were issued. On the other hand, they reasoned, this might just be a red herring to confuse spies, and they would perhaps be issued summer uniforms after they put to sea, and be on their way to the South Pacific. The A.W.O.L. soldier was the unit’s radio operator and George was needed to take his place.

George was upset to be leaving me alone, and phoned his folks to see if they could come to Vancouver. This was impossible but my mother said she would come before the time I was to be in the hospital, some time in July.

The shipping out was very secretive, and the men didn't know until they were a couple of days at sea where they were headed. They were relieved when they found it was not the hot jungle of the southern pacific islands, where there was intense fighting. The Aleutian islands were also partially occupied by the Japanese, and there had been many casualties on Attu Island when the Americans had retaken it recently, but they seemed less unpleasant than the humid southern islands. The force was stationed on the island of Attu until all preparations were made for the invasion of Kiska, still in Japanese hands. The climate there was damp, foggy, and windy. The American clothes, socks and mitts were made of cotton and not as suitable for the climate as Canadian uniforms would have been.

I had assumed George was in Alaska and it was some weeks before the news was broadcast that Kiska had been occupied by American and Canadian troops. They had found the Japanese recently gone, probably only hours before. Tea in thermoses left behind was still warm. The Canadian troops were stationed there for six months. Some Americans stayed on the island after that but the tide was beginning to turn against Japan and the serious danger of an attack from these islands against North America was beginning to be discounted.

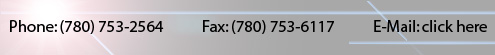

My mother arrived in Vancouver the week before Georgia’s birth in mid-July. It was wonderful for me to have her with me. She was probably more worried than I was about the arrival of the baby. I thought it was going to be an interesting event. I was only disappointed that George wasn't going to be there. (I don't mean in the delivery room as this wasn’t even imagined at the time.) In the labour room I explained to the nurse that I didn't want anesthesia. I wanted to be awake. She laughed. Natural childbirth was not in favour at the time, and after some hours of labour, a general anesthetic was administered. It was only after I wakened that I was told I had a baby girl. She weighed 5 pounds 5 ounces, was wrinkled and red, and had dark hair. I thought she was much prettier than any of the other babies in the ward. It had 16 beds, and was a noisy, busy place. The nurses were short-staffed, as many had left and joined the Armed Forces. We still were kept in bed for a week and only then allowed to sit up in a chair. The following day we would take a little walk. Most patients stayed 10 days. I was there for 12 as I ran a fever. A very new drug was given me, sulpha, the first of the antibiotic drugs. It involved round the clock administration —being wakened every few hours, but did quickly bring the fever to normal.

When Georgia was three weeks old, mother and I left by train for Provost. It seemed the wisest thing to do until I heard from George. I had sent a telegram, via the army post office to him, but it was a couple of weeks before he received it. I told him I'd given the baby both our names, Georgia Margaret. It wasn't what we’d planned but I had decided he should be remembered in this way, in the event of his not coming back. I didn't yet know where he was. We had talked of naming a girl Carolyn Anne, for both grandmothers, Carolyn being altered from Karalina, which I didn't much care for, and Carolyn a popular name at the time.

Our trip home to Provost was not unpleasant until we left the Edmonton station. A large group of American servicemen and construction workers on leave from work on the Alaska Highway came on board there. It was a raucous crowd. They carried bottles of whiskey, they laughed and sang, growing louder and less inhibited as the night wore on. Drinking was not supposed to be allowed on the train but the conductor was making no effort to control this group. Perhaps he was wise. I was actually frightened, especially for the baby. When mother asked him if there could be less noise, he just threw up his hands and shook his head. We were on a CN train, as the CP would have meant a change at Calgary as well as Edmonton and we’d picked the shorter route. We were happy to get off at Chauvin. It was 3 a.m. and Mr. Wahlberg, Vi’s (Ferris) father, was there to meet us, and took us to their home. My dad drove up the next morning and took us home to Provost. How nice it was to be there! Georgia and I were at mother and dad’s home rather than in our own house, as that house had been rented out during our absence.

George and I had been rather annoyed at the fact that his parents had rented out our house without consulting us. It was probably better that the house was occupied but we would have liked to make the decision ourselves, and when I arrived in Provost with my daughter I would have liked to go to our own home. My parents were welcoming and helpful but it was a disruption in their house, I'm sure. I took over the spare room for my and the baby's gear.

Letters and pictures were sent to George often, telling in detail each new accomplishment of the child he hadn’t seen. I knit sweaters and caps before her birth and made diapers and nighties.

Canadian Mother and Child was the recommended book at the time and I tried to follow it closely. It was then the belief that a baby should be on a strict schedule, fed at four hour periods, sleeping at regular times, and allowed to cry itself to sleep. A very cruel and unnatural method, I now think, but at the time I was determined to be a modern mother, and not allow my child to be spoiled by cuddling or using a pacifier.

Shortly before Christmas the Canadian troops were sent home from Kiska.

George came home on a two week furlough. I walked to the train to meet him — it was a cold bright morning. The train came in around six o’clock and how wonderful it was to see him jump off the step, far down the platform. We ran to meet each other, and I can now, more than 50 years later, close my eyes and feel his arms around me. He was thin and his arms were strong and hard as iron. We walked back to my folks’ house with our arms around each other, and cared nothing for curious looks of those who had met or got off the train. I could hardly wait for him to see the baby.

George spent much of his leave helping his father at The News office. I think we had Christmas dinner at each of the family homes. The unit was being stationed at Vernon, B.C. and when his leave was over Georgia and I went with him.

We lived that winter in one room, rented from a private home. It was poorly heated and we were often cold. I worried about the baby, but she seemed to thrive, and I pushed her in the carriage each day, bundled up warmly, for her afternoon airing, because that was what Canadian Mother and Child recommended. She was on a bottle now, canned milk diluted with boiled water, with corn syrup added. The bottles and nipples were boiled to sterilize them each morning, and diapers were washed by hand in the sink. Bedding for the crib was also washed each day as the “Book” disapproved of rubber pants, and soakers worn over the diapers were true to their name. They were soaked and the bedding as well. I don't think we ever went out in Vernon, and the only place I saw was the closest grocery store. The wartime baby carriage we were able to buy was not good quality and after a few weeks in wet snow the tires peeled off the wheels. They were made of pressed cardboard.

George's father suffered a serious heart attack in the spring and George was given compassionate leave to go home and help him. It eventually became a compassionate discharge from the army, when his father's health continued to fail. Newspapers were considered vital to the war effort. They were needed to encourage the spirits on the home front. By summer we were back in our own home. George's father was in and out of the hospital, and an invalid at home for the remainder of his life. He died later that year in 1944.

* Footnote:

The term Japanese Canadian was not one used at that time. Some were Japanese nationals but most were Canadian born or naturalized, and the second generation were all Canadians. Political correctness was not a wartime attitude. People called them "Japs" and they attached ill will to the name. In the same manner Germans were called "Huns" and both terms were used in the newspapers.

Another group that were given an unpleasant name were those who had been conscripted. These were mainly from the province of Quebec, where many young men felt no obligation to volunteer in what they believed to be an English war (although France was being overrun). The term given them was zombi, not used in the public press. The conscripts were assigned duty in Canada, not subject to duty overseas.

Full story and photos in November 7 edition of The Provost News.

Want to Subscribe to The Provost News? Click here.

|

|

|

|

|

|

Directory to be Located at Cemetery; Town to Help With Building

A directory of deceased people interred at the Provost Cemetery will be updated and a small building will be built on the grounds to house the information so the public can access it to locate certain graves.

There are hundreds of names for several cemeteries across the M.D. 52 that have already been recorded by Lois Acton who worked on a project of her own initiative, beginning in April 1987.

Full story and photos in November 7 edition of The Provost News.

Want to Subscribe to The Provost News? Click here.

|

|

Students Learn About Staging Productions

Full story in November 7 edition of The Provost News.

Want to Subscribe to The Provost News? Click here.

|

|

Street Spokesman

This week we ask : "Are You Glad Provost Has a Museum?"

. . . and we heard opinions from Clarence Taylor, Agnes Whiting, Doug Hall, Louise Schug, and Oscar Paulgaard.

Check out the November 7 edition of The Provost News for their answers.

Want to Subscribe to The Provost News? Click here. |

|

This, along with many other stories and pictures can be found in this week's edition of The Provost News.

Subscribe to the award winning paper by clicking on this link and following the instructions on our secure on-line ordering centre.

Take me to the Secure On-Line Ordering Centre

|

|